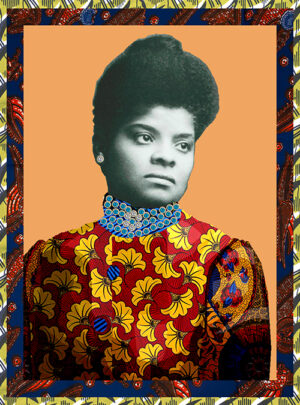

In honor of Ida B. Wells’ birthday today, I figured I’d share a few thoughts about her in light of what’s going on in the world.

Today I read about the protestors who were arrested at the attorney general’s home. Last week, Tobe Nwigwe dropped a fire ass song reminding us that her killers still ain’t been arrested. Before that, an officer involved was fired. And before that, “Breonna’s Law” was passed.

That’s because we showed up to protests for George Floyd, not to distract but to add to the conversation.

But what about Pamela Turner? And Korryn Gaines? Aiyana Jones, Atatiana Jefferson, and Shantel Davis? Why aren’t the sins against these black women and girls equally mourned and memorialized? Why aren’t they as reported on and rioted for?

Those who commit the murders write the reports. – Ida B. Wells

The same questions riddled Ida B. Wells, who was born enslaved in Mississippi in 1862 and died in 1931. Lemme bring it a lil closer to home. That means our grandmother’s grandmother also noticed that black women aren’t acknowledged the same way black men are. Our great-grandmothers did too, as did our grandmothers, mothers, and now us.

For a lil context, Ida dropped outta high school and became a teacher at 16 years old by lying and saying she was 18 after her parents died of yellow fever. She taught in Mississippi then Memphis. She was actually fired from in Memphis for writing about the poor condition of black schools. Afterwards, she made a living writing articles for different newspapers.

Her script flipped after her friend Thomas Moss shot a white man for harassing him. Moss and the two black men he was with were lynched. From that point forward, Ida was on a mission. She hit the road through the south (by her damn self) on trains mainly from one state to the next, following word of where a lynching was supposed to be happening.

I’ma do my best to highlight how dangerous her work was.

While white folk posed for pictures with “strange fruit,” Ida looked for folk who was willing to tell the truth about what happened. She was the detective who gave a damn about getting to the bottom of the story when the police did not, despite the fact that she wasn’t paid for it and could even be killed for it.

She also traveled to various cities and countries studying and discussing a concept that we now identify as “intersectionality” (thanks to Kimberlé Crenshaw). To best define intersectionality, consider this example:

Kimberlé, in her Ted Talk, asked everyone in the audience to stand. If she called a name that you didn’t know then you were to sit. Eric Garner was the first name called. Nearly everyone remained standing. Then Mike Brown. A few sat. Tamir Rice. Even more took a seat. After calling Freddie Gray’s name, she had everyone look around and notice that only about half of the room was still standing.

Then she went into the women’s names. Michelle Cusseaux. More than half of those still standing took a seat. Tanisha Anderson then Aura Russer and by the time she got to the last name, Meagan Hockaday, only four people were standing.

This is the same issue that Ida B. Wells advocated.

Just because a woman is black doesn’t mean that her struggles will be spoken for or even that her name will be remembered. You can’t make anyone understand your struggle. You can explain all year long but folk are either open to understanding and being an ally or they’re not.

When Tennessee lynched Eliza Woods in 1886, Ida made sure the world knew her name and what happened to her. She did the same for the 130 plus black women who were lynched between 1880 and 1930. Ida identified her purpose in the struggle as a teacher and organizer and applied pressure in the name of intersectionality—for black folk, yes, but for black women especially because she knew that…

Black women need Black women.

“Alone, she was not able to stop lynching,” a New York Times article wrote, “But with the help of other black women, she did put mob violence on the reform agenda and brought to light the rape of black women.”

Ida had a network of black women behind her and alongside her, listening to her, encouraging her, and even funding her. And with their support, she published the country’s first anti-lynching pamphlet called “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” This was one of the documents she took to Washington D.C. to demand change.

In addition to co-founding the NAACP, she also co-founded the Women’s Era Club, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, and a black woman’s suffrage group called the Alpha Suffrage Club. But as much work as Ida B. Wells put in for black women, rarely are people aware of her ongoing fight for black women’s rights—if they know who she is at all.

Though she was the most prominent black woman journalist and activist of her time, and pioneered protest strategies that would become crucial to the civil rights movement decades later, she is not nearly as well-known as her peers and friends Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. This taught me another valuable lesson:

Ida taught me that as a woman, when it comes to another woman (especially a woman of color), I have a responsibility to see her, to support her, and to relentlessly #SayHerName.

To read more historical bios like this, peep the journal entries over on my Krak Teet website.

Comments

One response to “Ida B. Wells on Black Women as Organizers and Victims”

Yes ma’am, I hear ya! #sayhername.